Banned Books Week.

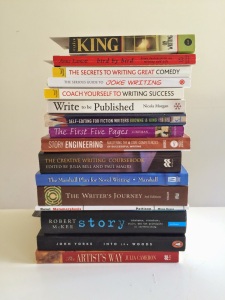

Celebrating the works of fiction and non-fiction that have drawn the ire of censors, Banned Books Week looks at a huge swathe of young adult titles as well as now recognised classics like James Joyce’s Ulysses and Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

It’s a pretty impressive though not particularly exclusive club.

The reasons for banning books are supposedly for sexually explicit content, cultural insensitivity, unsuitability for the cited age group, religious or political view points, violence, or offensive language. But ultimately, beneath all the complaints, what we really see when a book is challenged – or even banned – for its content, is fear.

Fear of the ideas a book contains. Fear of the ideas that inspired it. Fear of the ideas it might inspire.

I believe fear plays a crucial role in our relationship with books, one writers and readers must all be aware of even on some subconscious level. There’s fear in the writing, and in the act of writing, and in choosing a book, and in the act of reading, and in reacting to reading.

FOR ONE WEEK ONLY: Read all the lascivious literature you desire! Wishing everyone a scandalous #BannedBooksWeek. pic.twitter.com/V1J9vcwu6k

— Huffington Post (@HuffingtonPost) September 29, 2015

Engines. Wings. Windows. Wheels. Oxygen. Decompression. Bombs. Terrorism. Human error. Computer error. Impact.

It’s early morning. The sun is low but rising. The plane engines are a loud, featureless roar. I’m sitting in the window seat behind the left wing, counting off the myriad ways we could all die.

Engines. A fireball of burning fuel bursts through the seal of the doors. It melts the plastic of the table that a woman braces her head against.

Wings. The hydraulics have gone. We won't slow down.

Oxygen. We’re all sleepy, so slow and so sleepy as the tip of the plane noses downwards.

My brain on overdrive: echoes of stories reverberate in my head. German Airwings. The Hudson River. That writerly imagination making the possibility of flying in peace impossible. Oh sure there are other things I find scary or threatening. But the horrors of flying are always the same; fear burning away as ferociously as the images.

As foolish as it feels when my chest squeezes tight in the journey from terminal to malodorous tincan, I've used that same fear to develop tension and terror in my writing.

How does my protagonist feel when she steps into her lover’s house, hears the wrong music playing, sees his shadow dance beneath his feet? How does my reader feel as they discover each new clue to his predicament? Do they hang, tremulous as my protagonist? Can they feel the cord draw tight as they realise something is about to happen and it’s going to be terrible?

I’ve turned my almost risible fear into something useable.

Yet some of my other fears do precisely the opposite. They’re detrimental in the extreme and some of them I don’t even notice. Why? Because it’s not the sort of fear that inspires nightmares.

Just the kind that stops me from writing.

Now I understand your raised eyebrows but I’m talking the niggle in your head when you put pen to paper and you decide hmmm maybe not to include that scene or not to write that chapter because you think someone won't like it or it might cause offence. I'm talking about burying the kernel of a great idea for a novel because you know high elves and gargoyles are less popular than the strappings of a conventional mystery. Or deciding to couch a controversial issue behind a listicle or avoid writing about a subject because you're worried about the repercussions.

The same sort of fear that makes eighteen year olds feel self-conscious about picking books out of the young adult section or the majority of young fantasy and sci-fi readers more circumspect as they grow older, moving from speculative to more acceptable genres.

It’s self-censorship curated by a general understanding of convention.

We do it all the time, from not putting up that facebook status to not telling that joke.

Of course, some conventions are there for a reason. You don't throw a gratuitous f-word into Babbity Rabbit. And you don't stick sixty pages of explicit sex into a novel like Harry Potter (especially when the fandom will do it for you). And if dealing with religious or political material, maybe a cursory proof read would be good to ensure you're at least representing a valid concern.

But freedom of expression and speech are two things we should not take for granted. Not when there are writers being publicly flogged for their words or even being killed for them.

As Salman Rushdie said, “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

Stories have a special ability to allow divergence of thought, to challenge the everyday, to illuminate an issue and propose new answers. Books have exquisite power because of those stories. They address fear - react to and transform it. And not creepypasta stuff. What does Joyce do if not highlight the fears of his contemporaries? Or Junot Diaz in Drown? Or Irvine Welsh with well... everything? Sure obscenities abound in all the above, but it's fear that antagonises certain readers.

Plus, just because you don't like it doesn't make it 'bad'. Fiction you do not like is a route to books you may prefer. And not everyone has the same taste as you. We need to be aware of our fears and the things that make us stutter over the things we want to say or pause before we pick up a book or silence us when we should speak. Until we're aware of our fear we cannot truly understand what we are afraid of.

I struggle with fear sometimes. There are blogs I've scrapped because of what people might think. But I can't think that way and write what I want to write. I'm trying not to shy away anymore.

I know freedom of speech is one of those dark and twisty super slippery slopes. There's a time and place for self-censorship - even a time and place where we wish people would use it (ie. She Who Shall Not Be Named) - but it should be a choice made out of taste not fear, belief not ignorance. So you don't enjoy Frankie Boyle, or loathe Karin Slaughter's attention to gore. Don't read or watch them. But similarly, try not to label and moralise it for other people.

Oscar Wilde said “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

And if that means we must accept Fifty Shades of Grey has every right to be on bookshelves, so be it.

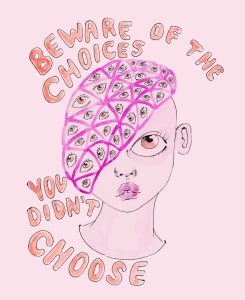

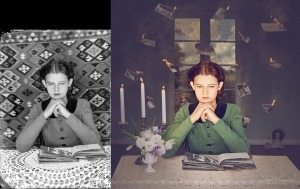

The pink illustrations and the featured image are by the supremely talented Ambivalently Yours (check out the tumblr page for more kick ass feminism in pink). Thank you for letting me use them in this blog!

And for a great article on the importance of reading and libraries check out Neil Gaiman's keynote speech on Why Our Future Depends on Libraries, Reading and Daydreaming.

Je serai poète et toi poésie,

SCRIBBLER