Of Dos and Don'ts

Because Writing Rules Suck

Oscar Wilde said: If at first you don't succeed, redefine success.

As a teenager, these words hung upon my wall (on one of those cheap bits of decorated metal you can find on Camden Market). As words to live by, it was right up there with ‘I will not let school get in the way of my education’ and ‘never trust someone who has not brought a book with them’.

When you think about it, redefinition of success is all literature is about.

Shakespeare redefined the sonnet. Laurence Stern redesigned Sentimentalism. Descartes revamped philosophy. Pope reconstructed Englishness. The Sage writers right up to T.S. Eliot and James Joyce and the Beats – were similarly about evoking a new, fresh sense of literary identity as well as society; they’re all showing how literature, and how we think about literature, needs to adapt and challenge and engage with the modern man and culture, our struggles, our failures, our limitations.

Take as an example Realism with a capital R. It started in France circa 1800 appealing to lofty ideals such as verisimilitude and poetic mimesis. Yet these ideas are ones Aristotle and Plato debated whilst they reclined and dined on grapes fed to them by small boys. When you try to read some of the novels produced through the Realist 'movement', you have the extremities of Balzac, Flaubert, George Eliot and Dostoevsky. The fact there are so many differences between them - Balzac claims to be a 'historian', Flaubert to have written about 'nothing' – only emphasises how even under the guise of a new ideal, in actuality they simply perpetuate what came before.

On a more contemporary level, let's remember The Matrix - it's Alice in Wonderland meets Plato.

It’s Hegelian thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

And we can break it down even further. There's an idea only a limited number of tales exist. For example, Christopher Booker claimed only Seven Basic Plots occur throughout literature. So whether you're a writer of crime fiction or romance, fantasy or drama, poetry or prose, all you're doing is redefining what is already written.

Once upon a time, this used to bother me. Actually, there are some days when it still does.

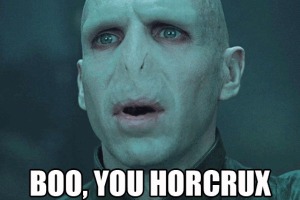

One of my earliest ‘novels’ (I was twelve, I’ve mentioned this attempt before) has a stone in it. This stone can contain a soul piece, though it takes a sacrifice in order to be able to use it. Should the sacrifice be made and the stone accepts the soul, then it keeps the person whose soul it belongs to safe from death.

Sounds familiar right?

Yeah, I thought so too. But there was twelve year old me, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire about to be released, with what amounts to a less evil version of a Horcrux and a character who needs to not be able to die for what little plot I came up with to work.

What was I to do when the inestimable Ms Rowling imagined an idea so eerily similar in the most famous series of our childhood?

At the time, I was aghast. I grumped. I scowled. I tucked the finished draft into a box and struggled with the reality of my concept not being half so original as I thought.

Typing over a decade later, there remains a small rankling child inside me for whom the coincidence still stings. However, the young adult version of me reacts differently. Thrilled at whatever hit-and-run literary smashup occurred, it opened me up to archetypes, theories of form and convention and, consequently, reinvention.

Because having a similar idea or concept or even an entire plot, doesn't mean that your story is any less interesting. Provided you possess a modicum of talent (and are not a twelve year old creating implausible beasts in a narrative thick with formlessness) there is the possibility of writing something that is yours. To take each word of the rule book and scatter them into a thing of imagination.

Genre fiction epitomises convention most overtly; it’s crystallised in your crime novels and romances, your sci-fi adventures and your battle-filled epics. It’s actually a really handy thing. The element of predictability and assumption in genre fiction means readers have an idea of what they’re buying. It also gives writers power. To disrupt and deny and disappoint all those presumptions.

The same goes for literary fiction, storytelling at all levels. Readers remember the writers who scupper those rules, who refute the dos and don’ts. They remembered the ‘but’, the volta, the turn of the piece.

Stories are built and broken on twists giving the finger to reader’s expectations. In doing so, authors not only make their work surprising but make us shudder, fret, cry, laugh, hold our breath and pray for another ending.

I never much liked rules.

|

Take them as guidelines and develop your own voice - no one else's.

|

There are some great words of advice out there for writers; Vonnegut’s lessons are invaluable, Chekov’s insights are peerless, and if you want to grasp how to be ruthless read King. But take them as guidelines, not rules. Use them in the editorial slice and dice. Don’t get caught up in worrying if the idea has appeared before.

There will be different characters, different styles of writing, different voices in your work.

So maybe think about the story and its predecessors, consider where the story's coming from and what you're working with. Perhaps examine ways you could improve upon before, and how it can be relevant now.

Vonnegut said: No modern, postmodern, metafictional, or any wildly unconventional story will succeed unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere.

Such a perfect insight, but it's not everything. It's the subversions of the old-fashioned plots that make a story successful, that create patterns of tensions and release.

There's only one rule in writing and that's to write. Go write. Fuck the rest of the rules and define your own success.

Read More, See More:

Atwood, Margaret. ‘Hair Jewellery’. The Art of the Tale: An International Anthology of Short Stories. Ed. Daniel Halpern. London: Penguin. 1987.

Booker, Christopher. The Seven Basic Plots. London: Continuum. 2004.

Boyle, T. Coraghessan. ‘Greasy Lake’. Greasy Lake and Other Stories. London: Penguin. 1986.

Chekov, Anton. ‘The Lady with the Little Dog’. The Lady with the Little Dog and Other Stories, 1896-1904. London: Penguin. 2002.

Freytag, Gustav. ‘Freytag’s Pyramid’, The Basic Formulas of Fiction. Ed. Foster-Harris. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. 1960.

Halpern, Daniel. The Art of the Tale: An International Anthology of Short Stories. London: Penguin. 1987.

Joyce, James. ‘Stephan Hero’, Moments of Moments: Aspects of the Literary Epiphany. Ed. Wim Tigges. Netherlands: Editions Rodopi B.V. 1990.

McEwan, Ian. ‘First Love, Last Rites’, The Art of the Tale: An International Anthology of Short Stories. Ed. Daniel Halpern. London: Penguin. 1987.

Mishima, Yukio. ‘Patriotism’, The Art of the Tale: An International Anthology of Short Stories. Ed. Daniel Halpern. London: Penguin. 1987.

Paz, Octavio. ‘My Life with the Wave’. Eagle or Sun?:Prose Poetry About Mexico trans. Eliot Weinberger. London: Peter Owen Publishers. 1990.

Vonnegut, Kurt. The Shape of Stories. The Man without a Country. http://visual.ly/kurt-vonnegut-shapes-stories-0

Je serai poète et toi poésie,

SCRIBBLER

No comments:

Post a Comment

Scribble Back